Bill Hipkiss (on the left) and his mate during the Depression years

In our writer’s group we were asked to write about an interesting object we have, or have had, in our garage that has a story to tell. I was reminded of a little primus stove I had for many years, which I have since passed on to my daughter.

This little stove is very neat and compact, and folds up to fit neatly into a tin smaller than a small shoe box. It was owned and used by my father in law, Bill Hipkiss, when, in his middle and later years, he spent countless hours out in the bush painting the scenery he loved so much. He would boil up his billy on the little primus stove and relax with a cuppa and his picnic lunch, perhaps sitting on an old tree stump or a canvas fold-up chair, enjoying the relaxation and peace he found in the bush.

When Bill visited us in Canberra he liked nothing better than a day out in the bush, sketching or painting, often with a grandchild by his side. He was a self taught artist, and, as well as paintings, pencil and charcoal sketches, he carved beautiful objects out of mallee stumps and tree bollards. Sadly, Bill had to sell most of his paintings and works of art, so there are only a few left in the family.

In this photo Bill is sketching in the Flinders Ranges near our camp site, watched by granddaughter Carrol.

A strong spirit

Bill Hipkiss was born on the 13th November 1905 in Birmingham in the United Kingdom. He was orphaned at the age of seven and was brought up and educated in an orphanage in Birmingham. From entries in the school log book it seems that Bill’s penchant for mischief started way back in his earlier years in the orphanage. In later years, when we knew him, he still had a wicked sense of humour and loved to enjoy a good laugh or a practical joke. In his teen years he was able to live with his older sister and family while serving an apprenticeship in the printing trade.

After the war, when Australia sought new settlers from Britain as a means of cementing the friendship between the two countries, both governments contributed to subsidised passage and offered loans to cover other costs. Perhaps attracted by the promise of guaranteed employment, good wages and plenty of opportunities, Bill, at the age of 21, set sail for Australia, landing at Fremantle in Western Australia in the mid 1920’s. After spending a few years in various odd jobs in the south-west of the state, he went north to Broome, working on the pearl luggers there for about four years.

One day he received a telegram from a fellow emigrant stating that business prospects were good in Victoria. As this was during the depression years of the early 1930’s work was scarce, and many hundreds of thousands of Australians faced the humiliation of poverty and unemployment. Bill decided to make the trip south and try his luck with his mate in Victoria. Undaunted by the huge distances involved, he set off.

The long journey

Bill walked from Broome to Port Hedland, a distance of approximately 750 kilometres. This was no mean feat, especially in those days when white settlements in those vast outback areas were few and far between. In Port Hedland he bought a second-hand bicycle and set out for Ararat via Meekatharra, Perth, Port Augusta, Adelaide and Bordertown. The entire journey took him a total of seventeen weeks, and at one stage he didn’t see a white person for a period of six weeks.

This was long before bitumen roads so the dust and dirt and rough riding must have been horrendous and added many layers of dust both to him and his gear. But being of good English stock, Bill would wash, shave and clean his boots without fail every day. His food was the usual tucker of the swagman in those Depression days, namely damper, billy tea and whatever meat he could get along the way. I wonder whether the little primus stove accompanied him on this journey.

He often related stories to his family of compassionate farmers who were willing to share shelter and whatever food was available. He told tales of the dust storms, the disappointing mirages, the excitement of civilization, and the times of despair and loneliness. He experienced the rejection of some, the suspicion of others and the pity of still others. He talked about the need to preserve water and the innovative ways of finding water, especially in the Nullabor. His children would sit enthralled as he recounted these stories over and over.

Bill persisted in his determination to keep to his pre-set goal of riding for so many hours each day, in spite of the pain, and this caused him to ultimately reach his destination in Victoria some seventeen weeks later.

Bill came to deeply love this sunburnt country despite his many struggles over the years, and this was seen in the beautiful scenes of the rugged outback captured in his paintings.

When, many years later, his son undertook the same journey his father travelled long ago (but in the relative comfort of a car), he experienced something of the harshness of the hot, dry north west as it is today. He was deeply challenged by the picture of a lonely, determined man fighting against such inhospitable country and seemingly insurmountable odds, but pressing on until he reached his journey’s end.

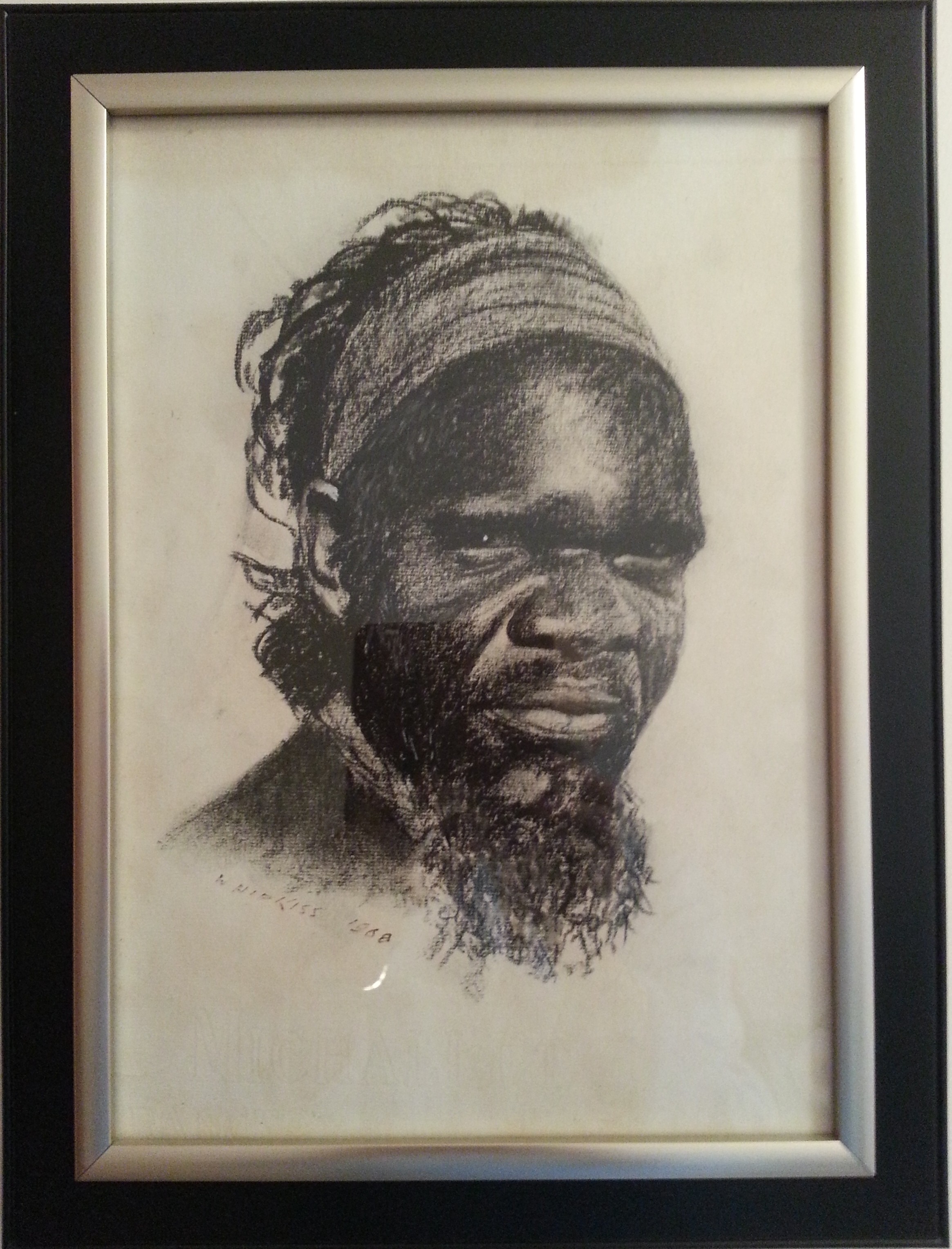

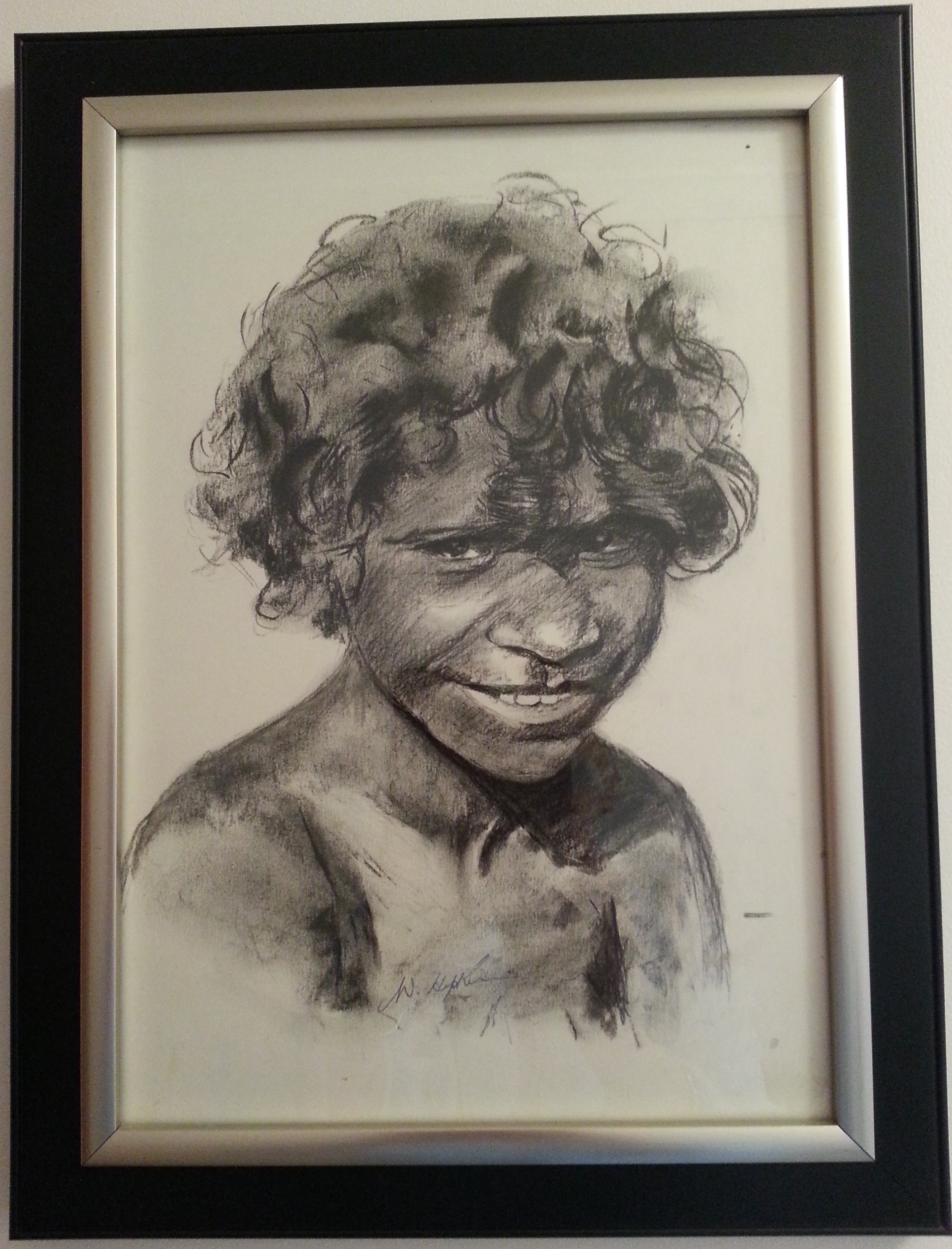

Two charcoal sketches I rescued from the floor of Bill’s shed.